|

|

HELP & INSTRUCTIONS

|

|

Coming Home from the Marshes

1886. Platinum print. | 19.8 × 28.9 cm (7 13/16 × 11 3/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

A group of four laborers, probably peat cutters, pose at the edge of a marsh in this image that was published in his 1886 book Life and Landscape of the Norfolk Broads. In this setting they embody an artistic ideal for Emerson, who believed that rural life and the landscape were the only legitimate subjects for art photographers. Emerson was also a vocal champion of naturalistic photography, which was based on a theory that sought to imitate the human eye's mode of perception, with the main subject in clear focus, and the periphery and distance less distinct.

Leopold Hamilton Myers as “the Compassionate Cherub”

About 1888-91. Platinum print. | 24.4 × 29 cm (9 5/8 × 11 7/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Untitled

About 1890. Platinum print. | 19.2 × 24 cm (7 9/16 × 9 7/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Redfield, a Philadelphia-based photographer, was drawn to nature as a subject and a source of inspiration. He frequently photographed the daily activities of farmers in rural Pennsylvania, arranging figures around animals in order to emphasize what he believed to be an innate connection between humans and the natural world. The warm tonalities and matte texture of the platinum process made it an ideal aesthetic choice for his subjects as it suggested a visual affinity with etchings and drawings enhanced by monochromatic washes of pigment.

Untitled

1894. Platinum print. | 23.2 × 18.3 cm (9 1/8 × 7 3/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Helen Sears

1895. Platinum print. | 22.8 × 18.7 cm (9 × 7 3/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Kelmscott Manor: In the Attics (2)

1896. Platinum print. | 19.9 × 14.9 cm (7 7/8 × 5 7/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

By harnessing natural light, rather than relying on darkroom manipulation to illuminate the architectural features of historic buildings, Evans became known for his unmanipulated platinum prints. Here his use of highly textured paper mimics the surface qualities of engravings, lithographs, and drawings, which were widely collected throughout the nineteenth century. Evans was keen on creating a visual connection between fine-art prints and his photographs.

La Cigale

Negative, 1901; print, 1908. Waxed gum bichromate over platinum print. | 31.4 × 27 cm (12 3/8 × 10 5/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

The artist’s title may reference Aesop’s fable of the grasshopper and the ant (in French, La cigale et la fourmi), in which the ant works all summer to build up its supplies for winter, while the grasshopper remains idle and unprepared for the season of cold weather. Allegorical subject matter, long associated with genre painting, was an important source for many Pictorialist photographers. Here the marked reduction of contrast and the dense blacks were achieved by applying a coat of pigment on top of the developed platinum print to mimic the qualities of layered brushwork.

Untitled

1900. Platinum print. | 17 × 11 cm (6 11/16 × 4 5/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Untitled

1900-1905. Platinum print. | 11.7 × 8.9 cm (4 5/8 × 3 1/2 in.) | 11.2 × 8.7 cm (4 7/16 × 3 7/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

The desire to emphasize the artist’s hand in individualized prints became a hallmark of photographers associated with Pictorialism. The application of coatings and the selective development of certain areas of a print distinguished their work from that of commercial practitioners. Keiley became well known for the use of glycerin, an organic compound that slowed the development of the image. For these two photographs, made from the same negative, a solution of developer mixed with glycerin was selectively applied with a brush to control the sections of the image that would be revealed.

Gertrude O’Malley and Son Charles

1900. Platinum print. | 20.2 × 15.6 cm (7 15/16 × 6 1/8 in.) | 20.3 × 13.5 cm (8 × 5 5/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

The artist likely applied chemical additives at different stages of developing and printing to create these visually distinct prints. Through experimentation with formulas for sensitizing solutions and developer baths, one can control the contrast, tonal range, and overall legibility of an image. The addition of mercuric chloride in the developer, for example, can result in a smoother grain, longer exposure scale, and an even warmer tone, but it also makes the print prone to accelerated aging that results in visible fading.

Untitled

1903. Platinum print. | 18.7 × 14.9 cm (7 3/8 × 5 7/8 in.) | 20 × 14.8 cm (7 7/8 × 5 13/16 in.) | 19.4 × 15.2 cm (7 5/8 × 6 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

This triptych featuring a young mother with her toddler is imbued with a sense of casual spontaneity and intimacy. Käsebier, who was a prominent commercial portrait photographer in New York, was also one of the most technically innovative Pictorialists. She regularly recorded members of her family in lively scenes that emphasized tender relationships and frequently showed her work at camera clubs, salons, and exhibitions dedicated to photography.

The Burning of Rome

1906. Gum platinum print. | 24.6 × 19.4 cm (9 11/16 × 7 5/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Twin Lakes, Connecticut

1916. Silver-platinum print. | 31.3 × 23.7 cm (12 5/16 × 9 5/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum © Aperture Foundation. Reproduced with permission.

The sparse composition and the oblique angle, achieved with an upturned lens, are two visual characteristics that signal a shift away from the aesthetic priorities of Pictorialism. This photograph demonstrates Strand’s newfound interest in modernism, a style and movement that abandoned traditional forms of representation in favor of new approaches. His use of a platinum and silver paper called Satista—named after Latin satis, meaning “sufficient,” and advertised as a cheaper substitute for pure platinum— exemplifies an interest in experimenting with the many options on the market.

Edward Weston

1921. Platinum print. | 24.1 × 15.6 cm (9 1/2 × 6 1/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum. Copyright status undetermined

Georgia O’Keeffe–Hands

1918. Platinum print. | 24.3 × 19.4 cm (9 9/16 × 7 5/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

The expressive hands of painter Georgia O’Keeffe, here contorted in front of her dark coat, became a recurring motif for Stieglitz, her husband. Palladium paper, introduced by the Platinotype Company in 1917 as an alternative to platinum, was praised in advertisements for having warm tones and a luminous quality. Stieglitz often complained to friends about the difficulties of making palladium prints that satisfied his high standards.

Hands Resting on Tool

1927. Platinum print. | 19.7 × 21.6 cm (7 3/4 × 8 1/2 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Landscape with Pump and Barn

About 1920-34. Platinum print. | 20.8 × 15.7 cm (8 3/16 × 6 3/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Untitled

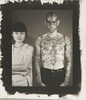

1986. Platinum and palladium print. | 24.3 × 19.4 cm (9 9/16 × 7 5/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum © Estate of Madoka Takagi. Reproduced with permission.

Gazing steadily into the camera, arms crossed, Takagi stands next to a shirtless man covered with elaborate tattoos. She captured this three-quarter length double portrait using the cable release in her right hand. Made shortly after she completed a course on platinum and palladium printing at Parsons School of Design, the photograph belongs to a series that features the artist standing next to people she met on the streets of New York.

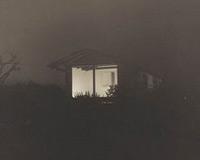

Dana Point, California

Negative, 2006; print, 2010. Platinum and palladium print. | 40.6 × 50.3 cm (16 × 19 13/16 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum © Scott. B. Davis. Reproduced with permission.

Based in San Diego, Davis has been working almost exclusively with platinum and palladium for over two decades. He notes, “My work with platinum and palladium printing explores how this process has the ability to simulate human vision under extremes of light and darkness. This photograph conveys our experience of seeing at night, particularly as the roofline dissipates into the late-evening shadows. Much as our ability to resolve fine detail is reduced in darkness, platinum and palladium prints uniquely capture this experience where visible objects disappear and enter the realm of imagination and mystery.” Gift of the artist

Untitled

2013-14. Platinum print. | 63.5 × 47.6 cm (25 × 18 3/4 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum. © James Welling. Reproduced with permission